Spirited away album download - share

Spirited Away

Spirited Away (Japanese: 千と千尋の神隠し, Hepburn: Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi, 'Sen and Chihiro’s Spiriting Away') is a 2001 Japanese animatedfantasy film written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki, animated by Studio Ghibli for Tokuma Shoten, Nippon Television Network, Dentsu, Buena Vista Home Entertainment, Tohokushinsha Film, and Mitsubishi.[6] The film stars Rumi Hiiragi, Miyu Irino, Mari Natsuki, Takeshi Naito, Yasuko Sawaguchi, Tsunehiko Kamijō, Takehiko Ono, and Bunta Sugawara. Spirited Away tells the story of Chihiro Ogino (Hiiragi), a 10-year-old girl who, while moving to a new neighbourhood, enters the world of Kami (spirits of Japanese Shinto folklore).[7] After her parents are turned into pigs by the witch Yubaba (Natsuki), Chihiro takes a job working in Yubaba's bathhouse to find a way to free herself and her parents and return to the human world.

Miyazaki wrote the script after he decided the film would be based on the 10-year-old daughter of his friend Seiji Okuda, the movie's associate producer, who came to visit his house each summer.[8] At the time, Miyazaki was developing two personal projects, but they were rejected. With a budget of US$19 million, production of Spirited Away began in 2000. Pixar animator John Lasseter, a fan and friend of Miyazaki, convinced Walt Disney Pictures to buy the film's North American distribution rights, and served as executive producer of its English-dubbed version.[9] Lasseter then hired Kirk Wise as director and Donald W. Ernst as producer, while screenwriters Cindy and Donald Hewitt wrote the English-language dialogue to match the characters' original Japanese-language lip movements.[10]

Originally released in Japan on 20 July 2001 by distributor Toho, the film received universal acclaim,[11] grossing over $352 million worldwide, and is frequently ranked among both the greatest animated films ever made and the greatest films of the 21st century.[12][13][14] Accordingly, it became the most successful and highest-grossing film in Japanese history with a total of ¥30.8 billion, overtaking Titanic (the top-grossing film worldwide at the time) in the Japanese box office.[15]

It won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature at the 75th Academy Awards,[16] making it the first and only hand-drawn and non-English-language animated film to win that award. It was the co-recipient of the Golden Bear at the 2002 Berlin International Film Festival (shared with Bloody Sunday), and is in the top 10 on the British Film Institute's list of "Top 50 films for children up to the age of 14".[17] In 2016, it was voted the 4th-best film of the 21st century by the BBC, as picked by 177 film critics from around the world, making it the highest-ranking animated film on the list.[18] In 2017, it was also named the second "Best Film...of the 21st Century So Far" by The New York Times.[19]

Plot[edit]

Ten-year-old Chihiro and her parents are traveling to their new home. They make a wrong turn and stop in front of a tunnel leading to what appears to be an abandoned village, which Chihiro's father insists on exploring despite his daughter's misgivings. While exploring, Chihiro finds an exquisite bathhouse and meets a boy named Haku, who warns her to return across the riverbed before sunset. However, Chihiro discovers too late that her parents have metamorphosed into pigs, and she is unable to cross the now-flooded river.

Haku finds Chihiro and advises her to ask for a job from the bathhouse's boiler-man, Kamaji. Kamaji asks Lin, a bathhouse worker, to send Chihiro to Yubaba, the witch who runs the bathhouse. Yubaba tries to frighten Chihiro away, but Chihiro persists, and Yubaba hires her. Yubaba takes away the second kanji of her name, Chihiro (千尋), renaming her Sen (千). Haku later warns her that if she forgets her name like he has forgotten his, she will not be able to leave the spirit world.

Sen is treated poorly by the other bathhouse workers; only Kamaji and Lin show sympathy for her. While working, she invites a silent creature named No-Face inside, believing him to be a customer. A "stink spirit" arrives as Sen's first customer, and she discovers he is the spirit of a polluted river. In gratitude for cleaning him, he gives Sen a magic emeticdumpling. Meanwhile, No-Face, imitating the gold left behind by the stink spirit, tempts a worker with gold and then swallows him. He demands food and begins tipping expensively. He swallows two more workers when they interfere with his conversation with Sen.

Sen sees paper Shikigami attacking a Japanese dragon and recognizes the dragon as Haku. When a grievously injured Haku crashes into Yubaba's penthouse, Sen follows him upstairs. A shikigami that stowed away on her back shapeshifts into Zeniba, Yubaba's twin sister. She transforms Yubaba's son, Boh, into a mouse and mutates Yubaba's harpy into a tiny bird. Zeniba tells Sen that Haku has stolen a magic golden seal from her, and warns Sen that it carries a deadly curse. Haku destroys the shikigami, eliminating Zeniba's manifestation. He falls into the boiler room with Sen, Boh, and the harpy, where Sen feeds him part of the dumpling, causing him to vomit both the seal and a black slug, which Sen crushes with her foot.

With Haku unconscious, Sen resolves to return the seal and apologize to Zeniba. Sen confronts No-Face, who is now massive, and feeds him the rest of the dumpling. No-Face follows Sen out of the bathhouse, regurgitating everything he has eaten. Sen, No-Face, Boh, and the harpy travel by train to meet Zeniba. Yubaba orders that Sen's parents be slaughtered, but Haku reveals that Boh is missing and offers to retrieve him if Yubaba releases Sen and her parents.

Zeniba reveals that Sen's love for Haku broke her curse and that Yubaba used the black slug to take control over Haku. Haku appears at Zeniba's home in his dragon form and flies Sen, Boh, and the harpy to the bathhouse. No-Face decides to remain with Zeniba. In mid-flight, Sen recalls falling years ago into the Kohaku River and being washed safely ashore, correctly guessing Haku's real identity as the spirit of the river.

When they arrive at the bathhouse, Yubaba forces Sen to identify her parents from among a group of pigs in order to break their curse. After Sen answers correctly that none of the pigs are her parents, she is free to go. Haku takes her to the now-dry riverbed and vows to meet her again. Chihiro returns through the tunnel with her parents, who do not remember anything after eating at the restaurant stall. When they reach their car, they find it covered in dust and leaves, but drive off toward their new home.

Cast[edit]

Production[edit]

Development and inspiration[edit]

| I created a heroine who is an ordinary girl, someone with whom the audience can sympathize. It's not a story in which the characters grow up, but a story in which they draw on something already inside them, brought out by the particular circumstances. I want my young friends to live like that, and I think they, too, have such a wish. |

| — Hayao Miyazaki[20] |

Every summer, Hayao Miyazaki spent his vacation at a mountain cabin with his family and five girls who were friends of the family. The idea for Spirited Away came about when he wanted to make a film for these friends. Miyazaki had previously directed films for small children and teenagers such as My Neighbor Totoro and Kiki's Delivery Service, but he had not created a film for 10-year-old girls. For inspiration, he read shōjo manga magazines like Nakayoshi and Ribon the girls had left at the cabin, but felt they only offered subjects on "crushes" and romance. When looking at his young friends, Miyazaki felt this was not what they "held dear in their hearts" and decided to produce the film about a young heroine whom they could look up to instead.[20]

Miyazaki had wanted to produce a new film for years, but his two previous proposals—one based on the Japanese book Kiri no Mukō no Fushigi na Machi (霧のむこうのふしぎな町) by Sachiko Kashiwaba, and another about a teenage heroine—were rejected. Miyazaki's third proposal, which ended up becoming Sen and Chihiro's Spirited Away, was more successful. The three stories revolved around a bathhouse that was inspired by one in Miyazaki's hometown. Miyazaki thought the bathhouse was a mysterious place, and there was a small door next to one of the bathtubs in the bath house. Miyazaki was always curious to what was behind it, and he made up several stories about it, one of which inspired the bathhouse setting of Spirited Away.[20]

Production of Spirited Away commenced in 2000 on a budget of ¥1.9 billion (US$15 million).[2]Walt Disney Pictures financed 10% of the film's production cost for the right of first refusal for American distribution.[21][22] As with Princess Mononoke, Miyazaki and the Studio Ghibli staff experimented with computer animation. With the use of more computers and programs such as Softimage 3D, the staff learned the software, but used the technology carefully so that it enhanced the story, instead of 'stealing the show'. Each character was mostly hand-drawn, with Miyazaki working alongside his animators to see they were getting it just right.[2] The biggest difficulty in making the film was to reduce its length. When production started, Miyazaki realized it would be more than three hours long if he made it according to his plot. He had to delete many scenes from the story, and tried to reduce the "eye candy" in the film because he wanted it to be simple. Miyazaki did not want to make the hero a "pretty girl." At the beginning, he was frustrated at how she looked "dull" and thought, "She isn't cute. Isn't there something we can do?" As the film neared the end, however, he was relieved to feel "she will be a charming woman."[20]Telecom Animation Film, Anime International Company, Madhouse, Production I.G, Oh! Production, and DR Movie helped animate the film.

Miyazaki based some of the buildings in the spirit world on the buildings in the real-life Edo-Tokyo Open Air Architectural Museum in Koganei, Tokyo, Japan. He often visited the museum for inspiration while working on the film. Miyazaki had always been interested in the Pseudo-Western style buildings from the Meiji period that were available there. The museum made Miyazaki feel nostalgic, "especially when I stand here alone in the evening, near closing time, and the sun is setting – tears well up in my eyes."[20] Another major inspiration was the Notoya Ryokan (能登谷旅館), a traditional Japanese inn located in Yamagata Prefecture, famous for its exquisite architecture and ornamental features.[23] While some guidebooks and articles claim that the old gold town of Jiufen in Taiwan served as an inspirational model for the film, Miyazaki has denied this.[24] The Dōgo Onsen is also often said to be a key inspiration for the Spirited Away onsen/bathhouse.[25]

Music and soundtrack[edit]

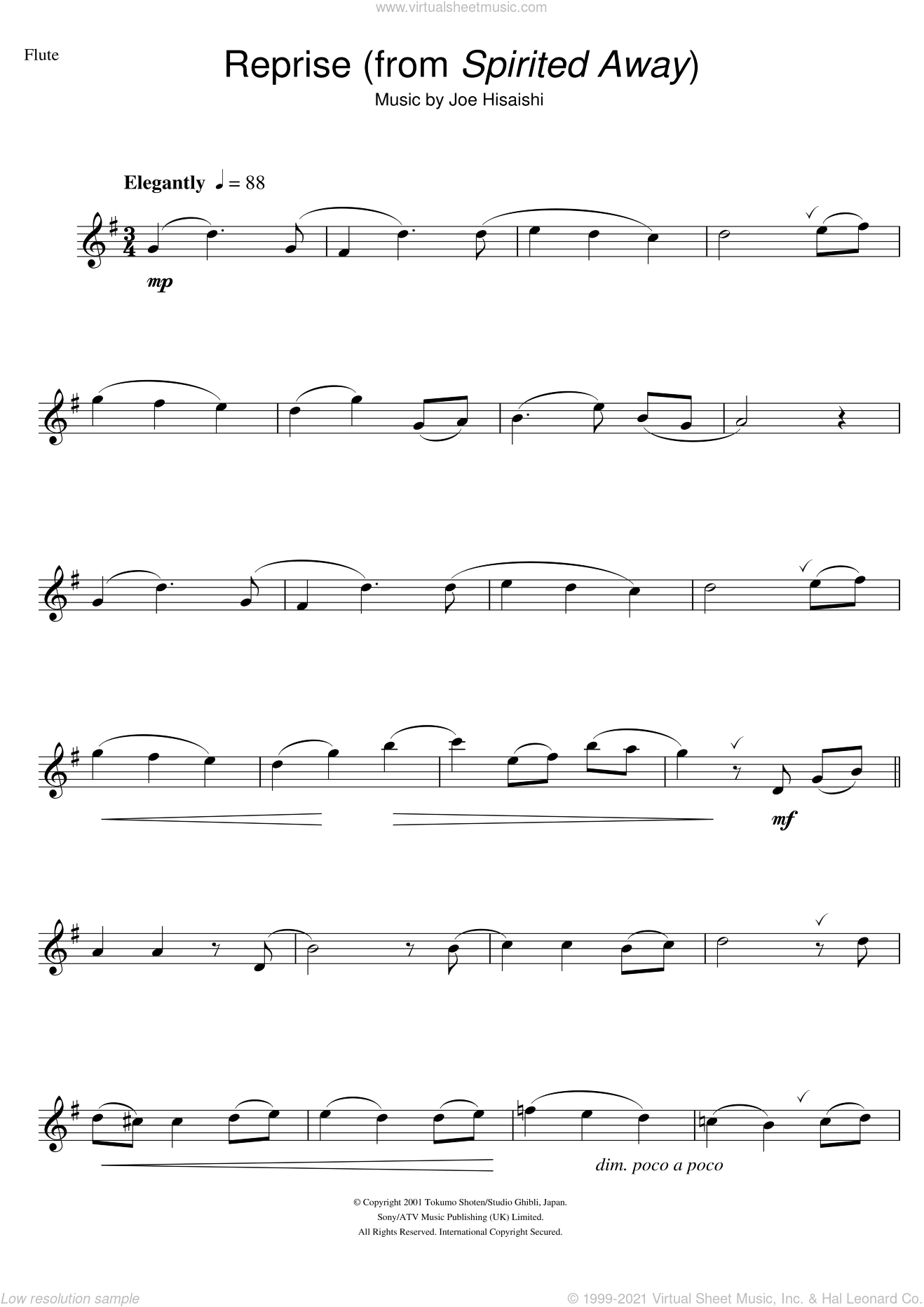

The film score of Spirited Away was composed and conducted by Miyazaki's regular collaborator Joe Hisaishi, and performed by the New Japan Philharmonic.[26] The soundtrack received awards at the 56th Mainichi Film Competition Award for Best Music, the Tokyo International Anime Fair 2001 Best Music Award in the Theater Movie category, and the 17th Japan Gold Disk Award for Animation Album of the Year.[27][28][29] Later, Hisaishi added lyrics to "One Summer's Day" and named the new version "The Name of Life" (いのちの名前, "Inochi no Namae") which was performed by Ayaka Hirahara.[30]

The closing song, "Always With Me" (いつも何度でも, "Itsumo Nando Demo", lit. 'Always, No Matter How Many Times') was written and performed by Youmi Kimura, a composer and lyre-player from Osaka.[31] The lyrics were written by Kimura's friend Wakako Kaku. The song was intended to be used for Rin the Chimney Painter (煙突描きのリン, Entotsu-kaki no Rin), a different Miyazaki film which was never released.[31] In the special features of the Japanese DVD, Hayao Miyazaki explains how the song in fact inspired him to create Spirited Away.[31] The song itself would be recognized as Gold at the 43rd Japan Record Awards.[32]

Besides the original soundtrack, there is also an image album, titled Spirited Away Image Album (千と千尋の神隠し イメージアルバム, Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi Imēji Arubamu), that contains 10 tracks.[33]

English adaptation[edit]

John Lasseter, Pixar animator and a fan and friend of Miyazaki, would often sit with his staff and watch Miyazaki's work when encountering story problems. After seeing Spirited Away Lasseter was ecstatic.[34] Upon hearing his reaction to the film, Disney CEO Michael Eisner asked Lasseter if he would be interested in introducing Spirited Away to an American audience. Lasseter obliged by agreeing to serve as the executive producer for the English adaptation. Following this, several others began to join the project: Beauty and the Beast co-director Kirk Wise and Aladdin co-producer Donald W. Ernst joined Lasseter as director and producer of Spirited Away, respectively.[34] Screenwriters Cindy Davis Hewitt and Donald H. Hewitt penned the English-language dialogue, which they wrote in order to match the characters' original Japanese-language lip movements.[10]

The cast of the film consists of Daveigh Chase, Jason Marsden, Suzanne Pleshette (in her final film role before her death in January 2008), Michael Chiklis, Lauren Holly, Susan Egan, David Ogden Stiers and John Ratzenberger (a Pixar regular). Advertising was limited, with Spirited Away being mentioned in a small scrolling section of the film section of Disney.com; Disney had sidelined their official website for Spirited Away[34] and given the film a comparatively small promotional budget.[22] Marc Hairston argues that this was a justified response to Studio Ghibli's retention of the merchandising rights to the film and characters, which limited Disney's ability to properly market the film.[22]

Themes[edit]

Supernaturalism[edit]

The major themes of Spirited Away, heavily influenced by Japanese Shinto-Buddhist folklore, center on the protagonist Chihiro and her liminal journey through the realm of spirits. The central location of the film is a Japanese bathhouse where a great variety of Japanese folklore creatures, including kami, come to bathe. Miyazaki cites the solstice rituals when villagers call forth their local kami and invite them into their baths.[7] Chihiro also encounters kami of animals and plants. Miyazaki says of this:

In my grandparents' time, it was believed that kami existed everywhere – in trees, rivers, insects, wells, anything. My generation does not believe this, but I like the idea that we should all treasure everything because spirits might exist there, and we should treasure everything because there is a kind of life to everything.[7]

Chihiro's archetypal entrance into another world demarcates her status as one somewhere between child and adult. Chihiro also stands outside societal boundaries in the supernatural setting. The use of the word kamikakushi (literally 'hidden by gods') within the Japanese title, and its associated folklore, reinforces this liminal passage: "Kamikakushi is a verdict of 'social death' in this world, and coming back to this world from Kamikakushi meant 'social resurrection.'"[35]

Additional themes are expressed through No-Face, who reflects the characters who surround him, learning by example and taking the traits of whomever he consumes. This nature results in No-Face's monstrous rampage through the bathhouse. After Chihiro saves No-Face with the emetic dumpling, he becomes timid once more. At the end of the film, Zeniba decides to take care of No-Face so he can develop without the negative influence of the bathhouse.[36]

Fantasy[edit]

The film has been compared to Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, as the stories have some elements in common such as being set in a fantasy world, the plots including a disturbance in logic and stability, and there being motifs such as food having metamorphic qualities; though developments and themes are not shared.[37][38][39] Among other stories compared to Spirited Away, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is seen to be more closely linked thematically.[38]

Yubaba has many similarities to the Coachman from Pinocchio, in the sense that she mutates humans into pigs in a similar way that the boys of Pleasure Island were mutated into donkeys. Upon gaining employment at the bathhouse, Yubaba's seizure of Chihiro's true name symbolically kills the child,[40] who must then assume adulthood. She then undergoes a rite of passage according to the monomyth format; to recover continuity with her past, Chihiro must create a new identity.[40]

Traditional Japanese culture and Western consumerism[edit]

Spirited Away contains critical commentary on modern Japanese society concerning generational conflicts and environmental issues.[41] Chihiro has been seen as a representation of the shōjo, whose roles and ideology had changed dramatically since post-war Japan.[41] Just as Chihiro seeks her past identity, Japan, in its anxiety over the economic downturn occurring during the release of the film in 2001, sought to reconnect to past values.[40] In an interview, Miyazaki has commented on this nostalgic element for an old Japan.[42]

Accordingly, the film can be partly understood as an exploration of the effect of greediness and Western consumerism on traditional Japanese culture.[43] For instance, Yubaba is stylistically unique within the bathhouse, wearing a Western dress and living among European décor and furnishings, in contrast with the minimalist Japanese style of her employee's quarters, representing the Western capitalist influence over Japan in its Meiji period and beyond. Along with its function within the ostensible coming of age theme, Yubaba's act of taking Chihiro's name and replacing it with Sen (an alternate reading of chi, the first character in Chihiro's name, lit. 'one thousand'), can be thought of as symbolic of capitalism's single-minded concern with value.[41]

The Meiji design of the abandoned theme park is the setting for Chihiro's parents' metamorphosis—the family arrives in an imported Audi car and the father wears a European-styled polo shirt, reassuring Chihiro that he has "credit cards and cash," before their morphing into literal consumerist pigs.[44] Miyazaki has stated:

Chihiro’s parents turning into pigs symbolizes how some humans become greedy. At the very moment Chihiro says there is something odd about this town, her parents turn into pigs. There were people that "turned into pigs" during Japan’s bubble economy (consumer society) of the 1980s, and these people still haven’t realized they’ve become pigs. Once someone becomes a pig, they don’t return to being human but instead gradually start to have the "body and soul of a pig". These people are the ones saying, "We are in a recession and don’t have enough to eat." This doesn’t just apply to the fantasy world. Perhaps this isn’t a coincidence and the food is actually (an analogy for) "a trap to catch lost humans."[43]

However, the bathhouse of the spirits cannot be seen as a place free of ambiguity and darkness.[45] Many of the employees are rude to Chihiro because she is human, and corruption is ever-present;[41] it is a place of excess and greed, as depicted in the initial appearance of No-Face.[46] In stark contrast to the simplicity of Chihiro's journey and transformation is the constantly chaotic carnival in the background.[41]

Environmentalism[edit]

There are two major instances of allusions to environmental issues within the movie. The first is seen when Chihiro is dealing with the "stink spirit." The stink spirit was actually a river spirit, but it was so corrupted with filth that one couldn't tell what it was at first glance. It only became clean again when Chihiro pulled out a huge amount of trash, including car tires, garbage, and a bicycle. This alludes to human pollution of the environment, and how people can carelessly toss away things without thinking of the consequences and of where the trash will go.

The second allusion is seen in Haku himself. Haku does not remember his name and lost his past, which is why he is stuck at the bathhouse. Eventually, Chihiro remembers that he used to be the spirit of the Kohaku River, which was destroyed and replaced with apartments. Because of humans' need for development, they destroyed a part of nature, causing Haku to lose his home and identity. This can be compared to deforestation and desertification; humans tear down nature, cause imbalance in the ecosystem, and demolish animals' homes to satisfy their want for more space (housing, malls, stores, etc.) but don't think about how it can affect other living things.[47]

Release[edit]

Box office and theatrical release[edit]

Spirited Away was released theatrically in Japan on July 20, 2001 by distributor Toho, grossing ¥30.4 billion to become the highest-grossing film in Japanese history, according to the Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan.[48] Its gross at the Japanese box office later increased to ¥30.8 billion.[15] It was also the first film to earn $200 million at the worldwide box office before opening in the United States.[49]

Disney's English dub of the film supervised by Lasseter, premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 7, 2002[50] and was later released in North America on September 20, 2002. Spirited Away had very little marketing, less than Disney's other B-films, with at most, 151 theaters showing the film in 2002.[22] After the 2003 Oscars, it expanded to as many as 714 theaters. The film grossed US$450,000 in its opening weekend and ultimately grossed around $10 million by September 2003.[51] Outside of Japan and the United States, the movie was moderately successful in both South Korea and France where it grossed $11 million and $6 million, respectively.[52] In Argentina, it is in the top 10 anime films with the most tickets sold.[53]

About 18 years after its original release in Japan, Spirited Away had a theatrical release in China on 21 June 2019. It follows the theatrical China release of My Neighbour Totoro in December 2018.[54] The delayed theatrical release in China was due to long-standing political tensions between China and Japan, but many Chinese became familiar with Miyazaki's films due to rampant video piracy.[55] It topped the Chinese box office with a $28.8 million opening weekend, beating Toy Story 4 in China.[56] In its second weekend, Spirited Away grossed a cumulative $54.8 million in China, and was second only behind Spider-Man: Far From Home that weekend.[57] As of 16 July 2019[update], the film has grossed $70 million in China,[58] bringing its worldwide total box office to over $346 million as of 8 July 2019[update].[59]

Home media[edit]

Spirited Away was first released on VHS and DVD formats in Japan by Buena Vista Home Entertainment on 19 July 2002.[60] The Japanese DVD releases include storyboards for the film and the special edition includes a Ghibli DVD player.[61]Spirited Away sold 5.5 million home video units in Japan by 2007,[62] and currently holds the record for most home video copies sold of all-time in the country.[63]

In North America, the film was released on DVD and VHS formats by Walt Disney Home Entertainment on April 15, 2003.[64] The attention brought by the Oscar win resulted in the film becoming a strong seller.[65] The bonus features include Japanese trailers, a making-of documentary which originally aired on Nippon Television, interviews with the North American voice actors, a select storyboard-to-scene comparison and The Art of Spirited Away, a documentary narrated by actor Jason Marsden.[66] In the UK, the film was released nationwide by Optimum Releasing on 12 September 2003,[67] and was later issued on DVD and VHS as a rental release through independent distributor High Fliers Films PLC after the film was released to theaters. It was later officially released on DVD in the UK on 29 March 2004, with the distribution being done by Optimum Releasing themselves.[68] In 2006, it was re-released as part of Optimum's "The Studio Ghibli Collection" range.[69]

The film was released on a Blu-ray format in Japan and the UK in 2014, and was released in North America by Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment on 16 June 2015.[70][71]GKIDS re-issued the film on Blu-ray and DVD on October 17, 2017.[72] On November 12, 2019, GKIDS and Shout! Factory issued a North-America-exclusive Spirited Away collector's edition, which includes the film on Blu-ray, and the film's soundtrack on CD, as well as a 40-page book with statements by Toshio Suzuki and Hayao Miyazaki, and essays by film critic Kenneth Turan and film historian Leonard Maltin.[73][74]

Along with the rest of the Studio Ghibli films, Spirited Away was released on digital markets for the first time, on 17 December 2019.

Reception[edit]

Critical response[edit]

Spirited Away has received significant critical success on a broad scale. On review aggregatorRotten Tomatoes, the film holds a 97% approval rating based on 187 reviews, with an average rating of 8.61/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "Spirited Away is a dazzling, enchanting, and gorgeously drawn fairy tale that will leave viewers a little more curious and fascinated by the world around them."[75]Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 96 out of 100 based on 41 critics, indicating "universal acclaim."[11]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film a full four stars, praising the work and Miyazaki's direction. Ebert also said that Spirited Away was one of "the year's best films," as well as adding it to his "Great Movie" list.[76]Elvis Mitchell of The New York Times positively reviewed the film and praised the animation sequences. Mitchell also drew a favorable comparison to Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass, as well as saying that Miyazaki's movies are about "moodiness as mood" and the characters "heightens the [film's] tension."[39] Derek Elley of Variety said that Spirited Away "can be enjoyed by sprigs and adults alike" and praised the animation and music.[3]Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times praised Miyazaki's direction and the voice acting, as well as saying that the film is the "product of a fierce and fearless imagination whose creations are unlike anything a person has seen before."[77]Orlando Sentinel's critic Jay Boyar also praised Miyazaki's direction and said the film is "the perfect choice for a child who has moved into a new home."[78]

In 2004, Cinefantastique listed the film as one of the "10 Essential Animations."[79] In 2005, Spirited Away was ranked by IGN as the 12th-best animated film of all time.[80] The film is also ranked #9 of the highest-rated movies of all time on Metacritic, being the highest rated traditionally animated film on the site. The film ranked number 10 in Empire magazine's "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema" in 2010.[81] In 2010, Rotten Tomatoes ranked it as the 13th-best animated film on the site,[82] and in 2012 as the 17th.[83] In 2019, the site considered the film to be #1 among 140 essential animated movies to watch.[84]

In his book Otaku, Hiroki Azuma observed: "Between 2001 and 2007, the otaku forms and markets quite rapidly won social recognition in Japan," and cites Miyazaki's win at the Academy Awards for Spirited Away among his examples.[85]

Accolades[edit]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^lit. "one thousand"

- ^lit. "flourishing swift-flowing amber [river] god"

- ^lit. "bathhouse granny"

- ^lit. "money granny"

- ^lit. "boiler grandad"

- ^lit. "faceless"

- ^lit. "faceless"

- ^lit. "blue frog"

- ^lit. "reception desk frog"

- ^lit. "Great White Lord"

-

-

-